Falcon 9 CRS-18 Launch, Photo Courtesy NASA

Falcon 9 Successfully Launches CRS-18 Payload For NASA

July 25, 2019 | Reported by Cliff Lethbridge

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket successfully launched the CRS-18 payload for NASA at 6:01 p.m. EDT today from Launch Pad 40 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Launch was delayed about 24 hours due to bad weather. CRS-18 consists of a SpaceX Dragon capsule bound for the International Space Station (ISS) with about 5,000 pounds of supplies, equipment and experiments. The Dragon capsule flown today is making its third flight, having supported the CRS-6 mission in April, 2015 and the CRS-13 mission in December, 2017. The Falcon 9 first stage booster flown today made its first flight and was successfully recovered with a landing at Landing Zone 1 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. The CRS-18 payload successfully separated from the Falcon 9 second stage about nine minutes after liftoff, and will reach ISS on Saturday, July 27.

Falcon 9 At Booster Engine Cutoff, Photo Courtesy Lloyd Behrendt/Spaceline

This is the eighteenth of 20 SpaceX missions to ISS currently contracted with NASA under the Commercial Resupply Services contract, however additional missions are expected as the space agency has extended the SpaceX contract through at least 2024. CRS-18 carries dozens of experiments in support of more than 250 investigations currently ongoing aboard ISS. Highlights of the experiments launched today include BioRock, an investigation of how microbes attached to rocks are able to break down rock and extract minerals. The BioFabrication Facility (BFF) will investigate methods for the 3-D printing of living tissue, perhaps one day allowing the fabrication of human organs. A Goodyear Tire experiment evaluates the creation of silica fillers and their properties. The Space Moss experiment will determine the possibility that mosses can provide food and oxygen for crews on long duration space missions.

Falcon 9 Booster Approaches Landing, Photo Courtesy Lloyd Behrendt/Spaceline

Cell Science-02 will investigate the effects of microgravity on healing and tissue regeneration, with a focus on how better bones can be generated in space, as bone loss remains a serious concern on long duration space flights. An important piece of hardware carried on CRS-18 is the International Docking Adapter (IDA), which will serve as a physical point for connecting spacecraft to ISS. IDA technology is more sophisticated than in the past, and among other things will facilitate communication between the IDA and spacecraft using lasers and sensors, enabling automated alignment and connection to ISS. The CRS-18 Dragon capsule will return to Earth with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the Baja Coast carrying about 3,300 pounds of cargo following a four-week stay at ISS.

Falcon 9 Booster Lands At Landing Zone 1, Photo Courtesy SpaceX

Falcon 9 CRS-18 On Launch Pad 40, Video Capture Courtesy SpaceX

Falcon 9 Launch Scrubbed Due To Bad Weather

July 24, 2019 | Reported by Cliff Lethbridge

This evening's scheduled launch of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying the CRS-18 payload for NASA has been scrubbed due to bad weather. Launch had been scheduled for 6:24 p.m. EDT but was officially scrubbed 30 seconds before launch. Primary weather concern was thunderstorms in the vicinity of the launch pad. Launch has been rescheduled for 6:01 p.m. EDT on Thursday, July 25, 2019. Launch will occur from Launch Pad 40 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. CRS-18 consists of a SpaceX Dragon capsule bound with supplies, experiments and equipment for the International Space Station.

Spaceline Remembers Apollo 11 On Fiftieth Anniversary

July 16, 2019 | Reported by Cliff Lethbridge

It was one of those special moments. You remember where you were, what you were doing and what you witnessed when that event occurred. Such was the case with Apollo 11, which was to date the most challenging and exciting journey in the history of mankind. We may send people to the Moon again, maybe soon, but there will never be another Apollo 11, the first manned lunar landing. I envy my friends who grew up on Florida's Space Coast and who witnessed first hand this historic launch, which occurred 50 years ago today. I grew up in New Jersey, so I had to rely on the television for all of the space happenings. I cannot say that at age eight I remember watching the Apollo 11 launch or lunar landing, but I vividly recall lying on my stomach watching Neil Armstrong's first footstep on the Moon via a portable black and white television. That event took place at 10:56 p.m. on July 20, 1969 and I can also recall how wonderful it was to stay up late! We trust that you may be old enough to have your own special Apollo 11 memories, and just to refresh your memories we have reproduced our Apollo 11 Fact Sheet from www.spaceline.org here. Hope it helps you recollect, and may God bless all of our readers, and there are many, who dedicated their lives to make the United States the greatest of all space-faring nations. Long live the memory of Apollo 11.

Apollo 11 Crew Portrait, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Apollo 11 Fact Sheet

Written and Edited by Cliff Lethbridge

Apollo 11 (NASA Code: AS-506/CSM-107/LM-5)

Apollo 11 Crew Departs For Launch Pad, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Launch Date: July 16, 1969

Launch Time: 9:32:00 a.m. EDT

Launch Site: Launch Complex 39, Launch Pad 39A

Launch Vehicle: Apollo-Saturn V AS-506

Apollo 11 Launch, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Command Service Module: CSM-107

Command Module Nickname: Columbia

Lunar Module: LM-5

Lunar Module Nickname: Eagle

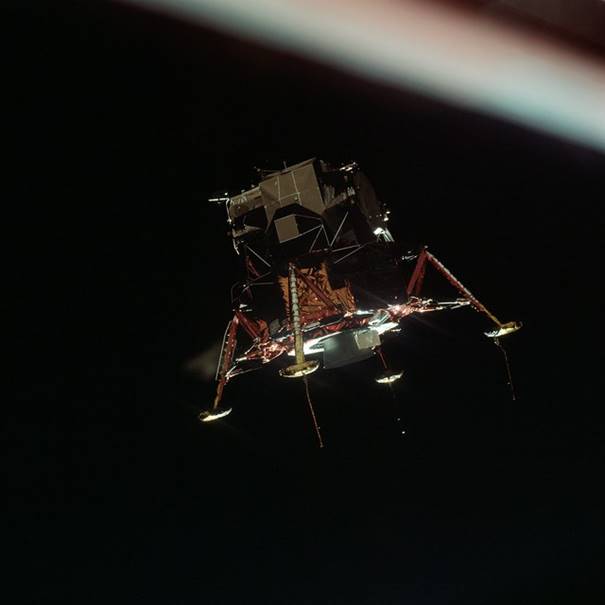

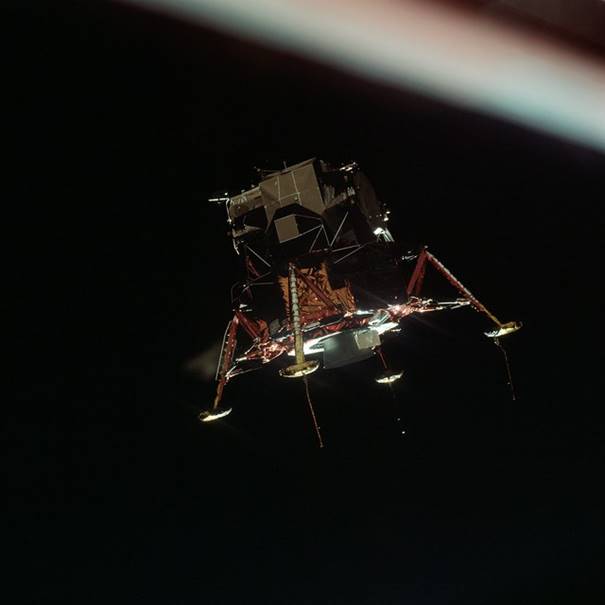

Eagle Departs CSM For The Moon, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Crew:

Neil A. Armstrong, Commander

Michael Collins, Command Module Pilot

Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin, Jr., Lunar Module Pilot

Back-up Crew: Lovell (CDR), Anders (CMP), Haise (LMP)

Mission Duration: 8 Days, 3 Hours, 18 Minutes, 35 Seconds

Number of Lunar Orbits: 30

Recovery Date: July 24, 1969

Recovery: U.S.S. Hornet (Pacific Ocean)

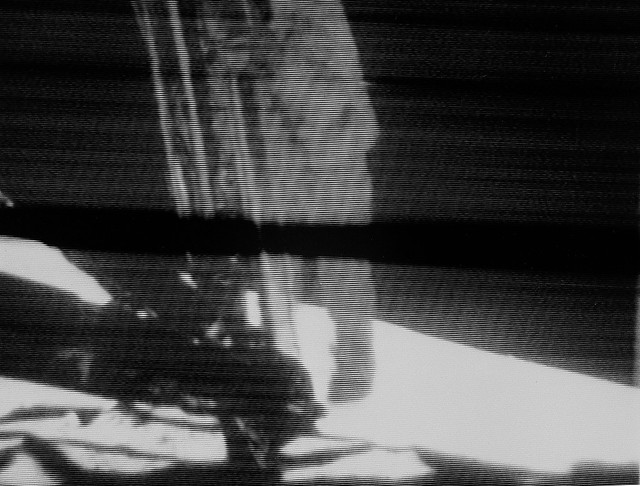

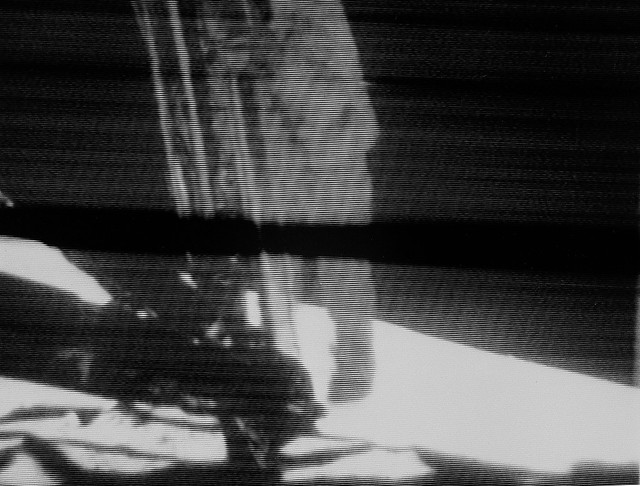

Neil Armstrong Sets Foot On The Moon, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Mission Summary:

Climaxing with the first manned landing on the Moon, Apollo 11 will likely remain the most famous and widely publicized space flight of all time. All mission elements went according to plan, and only one of an anticipated four trajectory correction firings from the CSM engine was needed to keep the Apollo 11 spacecraft pointed toward its historic rendezvous with the Moon. At about 55 hours into the flight, the Apollo 11 crew participated in a live television broadcast which lasted 96 minutes. The broadcast, carried on commercial television, whet the appetite of a huge audience anxiously awaiting the lunar landing which was by now just two days away.

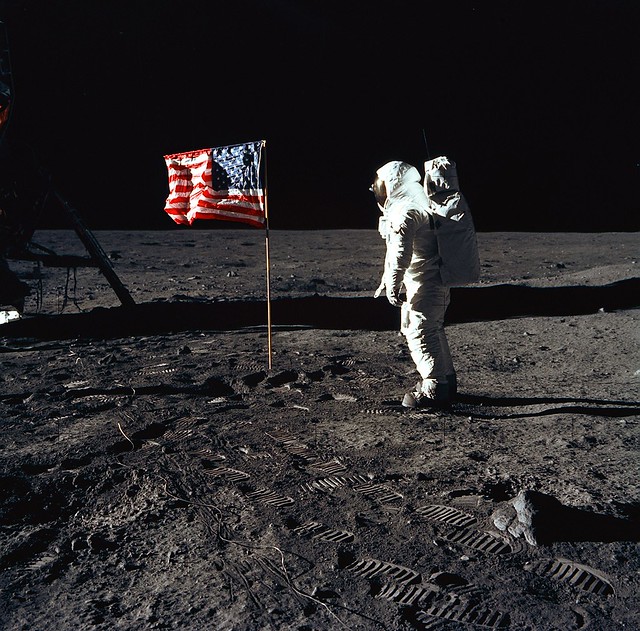

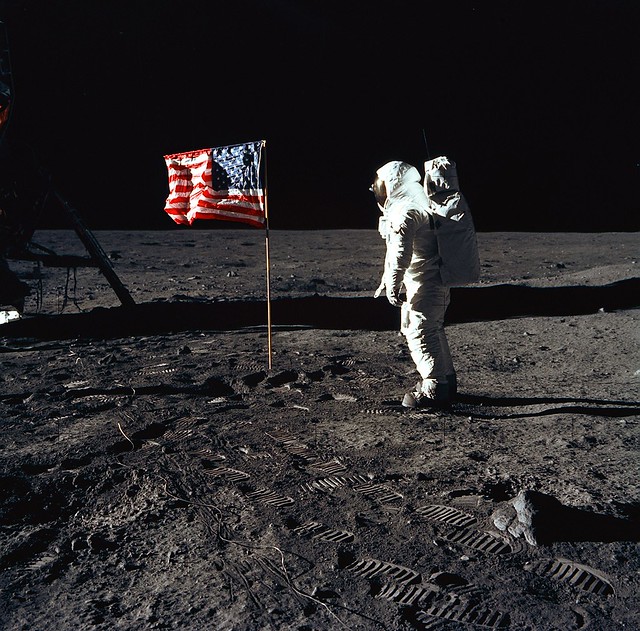

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin With American Flag, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Four days into the flight, the Command Service Module (CSM) engine fired twice to place the Apollo 11 spacecraft in a low-lunar orbit. Armstrong and Aldrin transferred to the Lunar Module (LM), which undocked from the CSM and dropped toward the lunar surface after a set of visual inspections and checks. The descent took a nailbiting 12.5 minutes and was not without high drama which heightened the tension surrounding a mission already supercharged with excitement.

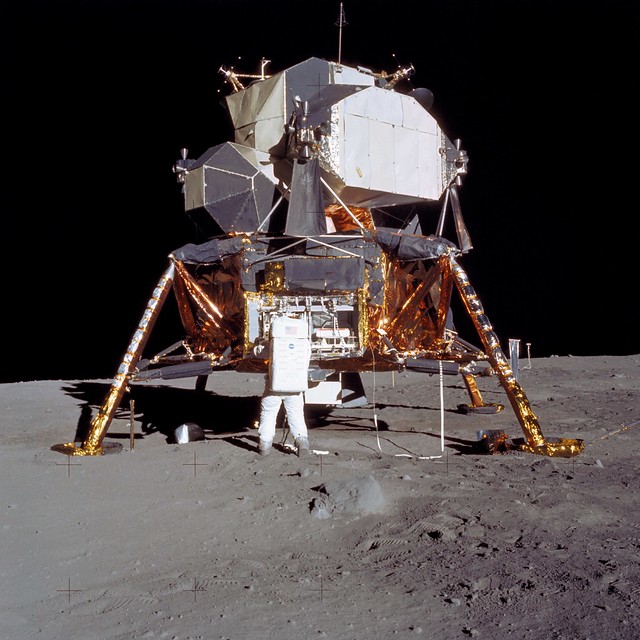

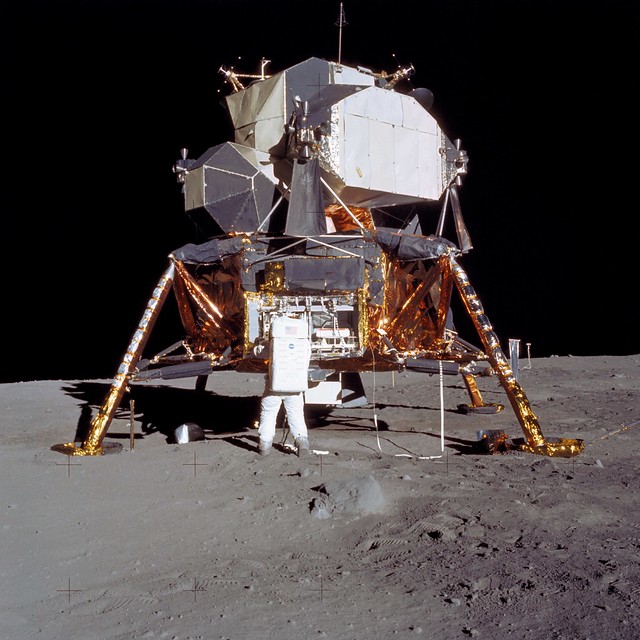

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin At Eagle, File Photo Courtesy NASA

At a distance of about 6,000 feet from the Moon, an alarm light came on in the LM. Mission controllers said a computer overload had occurred which would not hinder the landing. At about 3,000 feet above the lunar surface, a second alarm light came on, followed by four more in the next four minutes. All alarms were waived by mission managers. However, the astronauts aboard Eagle were distracted and failed to notice until 2,000 feet from touchdown that the LM automatic landing system had selected a landing site that was too rocky. At just 300 feet above the lunar surface, Armstrong took manual control of the LM and piloted the spacecraft at about 55 m.p.h. to select a suitable landing site.

Eagle Departs Moon For CSM Docking, File Photo Courtesy NASA

A warning that less than 5% of descent fuel remained was indicated, giving Armstrong 94 seconds to land the spacecraft prior to an abort and return to the CSM. As the LM approached a suitable landing site, lunar dust was kicked up, reducing Armstrong's visibility to a few feet. At 33 feet above the lunar surface, the LM lurched dangerously, but Armstrong continued to gingerly guide the spacecraft toward a touchdown which was becoming increasingly hazardous. Nevertheless, Eagle landed in the Sea of Tranquility at 4:17:43 p.m. EDT on July 20, 1969. Just 20 seconds of descent fuel remained for the landing, which occurred about four miles from the original target.

Apollo 11 Command Module Hoisted Aboard Recovery Vessel, File Photo Courtesy NASA

The LM astronauts donned spacesuits and were prepared to step out onto the Moon about 6.5 hours after lunar touchdown. Armstrong placed a television camera onto the LM ladder, then set foot on the Moon at 10:55:15 p.m. EDT on July 20, 1969, as the astronaut uttered his immortal phrase, "That's one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind." The event was viewed live on television by an estimated 500 million people. Armstrong almost immediately scooped up some lunar soil and placed it in a Teflon bag attached to his spacesuit. Aldrin followed about one hour thereafter. The two men set up an American flag and deployed a number of scientific experiments including a seismometer, laser reflector and solar wind detector. The experiments were deployed in what was called the Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package (EASEP). The astronauts also gathered about 50 pounds of lunar rock and soil samples, and had a chance to speak live with President Richard M. Nixon.

President Nixon Meets Quarantined Astronauts, File Photo Courtesy NASA

The total time of the first human lunar excursion was 2 hours, 32 minutes. Just one lunar excursion was allotted to this mission. The LM lifted off after a lunar stay of 21 hours, 36 minutes and re-docked with the CSM for a return to Earth. The return flight and splashdown were flawless. Splashdown occurred at 12:49 p.m. EDT about 12 miles from the recovery vessel. For the first time, U.S. astronauts were quarantined after their return to Earth. A mobile quarantine facility was used for the first time, as was the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, where the Apollo 11 crew remained isolated for about three weeks.

Apollo 11 Astronauts In New York Ticker Tape Parade, File Photo Courtesy NASA

Abort Test Booster Launches Launch Abort System, Photo Courtesy NASA

NASA Successfully Tests Orion Launch Abort System

July 2, 2019 | Reported by Cliff Lethbridge

Many onlookers suspected that a rocket had exploded, but that was not the case. Rather, NASA successfully test flew the Orion Launch Abort System (LAS) in a simulated launch failure with a launch from Launch Pad 46 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station at 7:00 a.m. EDT today. The LAS was carried aloft by an Abort Test Booster (ATB). Key flight objectives are to demonstrate abort capability at maximum aerodynamic pressure, determine the stability characteristics and reorientation dynamics of the LAS, obtain LAS structural loads and structural integrity data, obtain interface data for the LAS and crew module, demonstrate the LAS separation mechanism and gather information on the LAS external environment, including acoustics, aerodynamics, thermal data and acceleration.

LAS Speeds Away From ATB, Photo Courtesy NASA

A key component of the ATB is its powerplant, an SR118 rocket motor adapted from the first stage of a Peacekeeper missile. The rocket motor has a length of 334 inches and a diameter of 92 inches. The rocket motor is encased in an aerodynamic shell used to match the diameter of the Orion crew module. The total vehicle has a length of about 36 feet and a diameter of about 18 feet and produced about 500,000 pounds of thrust at launch. The ATB was ballasted to make it heavier, lest it carry the LAS aloft too quickly. The ATB was procured by the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center Rocket Systems Launch Program and built by Northrop Grumman.

LAS Firing, ATB And Crew Module Jettison, Photo Courtesy Lloyd Behrendt/Spaceline

Key components of the LAS, built by Lockheed Martin, include a lightweight composite fairing assembly that covers the crew module to protect it from the environment around it. The LAS has a launch abort tower with three separate motors. The abort motor fires with a thrust of 400,000 pounds and is designed to pull the crew module away from the launch vehicle on the launch pad or during ascent. The attitude control motor is fired to stabilize the crew module. Both the abort motor and attitude control motor are manufactured by Northrop Grumman. The jettison motor is fired to pull the LAS away from the crew module and is manufactured by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

LAS Firing And ATB Descent, Photo Courtesy Cliff Lethbridge/Spaceline

The ATB launched the Orion test capsule and LAS. At Launch Plus 55 Seconds when the vehicle was at an altitude of 31,000 feet, the abort sequence was initiated. The LAS abort motor was fired, pulling the crew module away from the ATB and gaining more than two miles in altitude in about 15 seconds. At an altitude of 43,000 feet, the LAS attitude control motor was fired in order to orient and flip the crew module to assure safe separation. At an altitude of 44,000 feet, the LAS jettison motor fired to pull the LAS tower assembly away from the crew module, releasing the capsule to descend toward the ocean. During the capsule's descent, 12 data recorders were jettisoned, all of which were recovered at sea. Neither the crew module nor the LAS were recovered, as parachutes were not flown. NASA cited cost savings of not employing parachutes and extensive data already received from previous parachute tests. Today's successful test paves the way for Artemis-1, an unmanned flight of an Orion capsule around the Moon.

Spent LAS Approaches Ocean Impact, Photo Courtesy Lloyd Behrendt/Spaceline